Inclusive design myth busting

COVID-19 has pushed more people online than ever before. Three times more 70-year-olds have registered for online banking than the year before. For those of us who the web is largely built for this has been an inconvenience but for those who have been excluded from the web due to age, disability, poverty, literacy, neurodiversity, confidence or whole host of other reasons it’s been incredibly difficult.

Doing research for and designing services that are inclusive is a big part of my work, so it’s something I think about a whole lot. But I know it’s not at the top of everyone’s mind. That’s why, along with some of my brilliant colleagues, I run inclusive design workshops for anyone involved in services that have some or all of their interactions online. We’ve run these workshops with designers, researchers, coders, and people working in communications internally and externally with participants across government and financial sectors so far.

Through those workshops we’ve busted a lot of myths about inclusive design and I wanted to share some of those with you here.

An example of some of the feedback from one of our workshops

This is an extended version of a piece that I put together for ENGINE’s blog, if you’re short on time feel free to head on over and read the highlights.

Inclusion is only about making things accessible to people with disabilities, right?

Making things accessible to people who live disabilities is hugely important. We need to consider how people who have a range of abilities different to our own are able to engage with and feel included in the work we do.

In order to do that we need to go beyond just thinking about perhaps the obvious things you imagine as disabilities, and instead consider a whole range of barriers that might typically make it harder for someone to use services online. That means thinking about how people across the spectrum of age, gender, race, neurodiversity, literacy, access and confidence amongst lots of other factors can be included in your service. It also means thinking about how you might, unintentionally, be excluding people.

When we make services that are inclusive and flexible to as wide a range of people as possible, we’re making them better for lots of people, not just those who you might have thought about facing barriers to access.

But surely that’s still only small number of people?

There are far more people than you might expect. Let me hit you with some statistics…

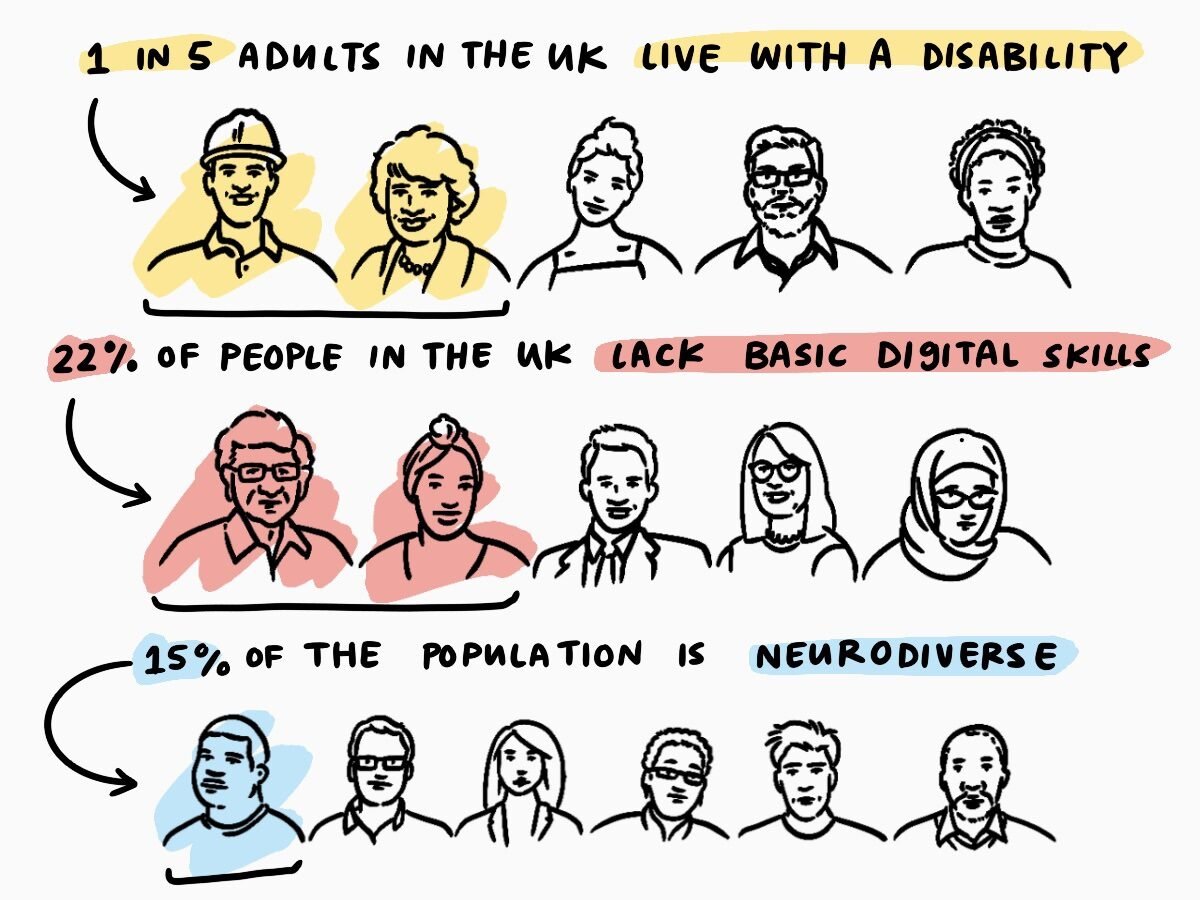

In the UK alone there are around 14.1 people who live with a disability, that’s around 1 in 5 working age adults and just under half of people old enough to receive a pension.

Around 15% of people are neurodivergent, including those who are autistic or dyslexic, which means that their brains function, learn and process information in ways different to what society expects.

Then 22% of people in the UK lack the digital skills they need for everyday life, the skills and confidence you might take for granted if you’re reading this blog post.

When we’re thinking about who might use our services online, we also need to think about people with disabilities that might be temporary (like breaking your arm for example!) and situational (like having to carry a crying baby in one arm).

So, a huge number of people are often, unfairly, excluded from services.

Isn’t most of the internet inclusive as standard?

Not at all, actually, only 2% of the world’s most popular websites actually meet the legal requirements for accessibility. So, 98% do not. That’s before you think about how inclusive their content and design is once you can access it.

Well, people can just get someone to help them can’t they?

Particularly in light of COVID-19, where many of us where isolated from our usual support networks, it’s wrong to assume that everyone has access to support. There are many things we all want to, and should, have the ability to do on our own. So, we should be striving to create inclusive services which empower people to access what they want and need on their own terms.

Is there a checklist I can follow?

There are some basic accessibility guides that you should definitely follow. GDS (Government Digital Services) break these down in a really easy to understand way and WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) offer a brilliant guide for testing online services for those who want to get deeper.

But inclusion goes beyond that. It’s about really understanding who’s using your services (and who might want to or need to) and how the want to engage with what you’re putting out into the world.

Often making things simpler and easier for people who typically face barriers to accessing digital services makes those services easier for everyone. But the idea that one solution will be universal isn’t quite true. That’s a myth I bought into at the start of my career. Universal design sounds great and really easy to scale. However, we all have different needs and sometimes flexibility and specificity are the best way to support those needs. I learned a lot about that from Sarah Hendren’s brilliant book ‘What can a body do?’. The example that we usually turn to discussions at work is the idea that phone support is a great way to offer human assistance for those who aren’t digitally confident, but it’s also awful for those who are anxious or living with Alzheimer’s where it can be stressful to talk on the phone and hold conversations in your memory.

So, if the designer on the project knows about this stuff it’s all sorted?

Everyone involved in services needs to be aware of and asking questions about inclusion. So often the people who make design decisions aren’t just designers but stakeholders with purchasing power, developers who actually build and test services, researchers and strategists who give direction to projects. That’s why the workshops we’ve been running are aimed at broad understanding and getting conversations started across businesses.

Okay, but surely this is going to cost money, is it commercially viable to improve services?

Let’s be honest, working inclusively does require an investment. Making sure you’re doing high quality research and design with users with a range of abilities takes time, money and effort.

But it’s an investment that will repay you many times over. Services that are easy to use require less support to fix errors and answer queries. They’re also more likely to get a share of the £11,750,000,000 (that’s over £11 billion with a b) estimated spending power of assisted digital users. I know from experience testing services and running inclusive design workshops the power of a hard to use service to turn people away, but also the loyalty (and genuine joy) that comes with using something that makes you feel included.